instructAR – Enhancing Teaching Experience with AR

Derek Zhang (838C) and Chih-Yun Tseng (498F)

Welcome to our Advances in XR (CMSC498F/CMSC838C) final project instructAR.

Table of contents

- Introduction

- Project Description

- Related Work

- Methodology

- Results & Analysis

- May 18th Project Presentation

- April 28th Project Progress Report

- April 5th Project Proposal

- Instructions

- Links to our source code

- References

- Acknowledgements

Introduction

Imagine you’re a teacher in a classroom of students wearing masks. You have no idea if they understand the lecture. Our project idea is to create a teaching aid using AR that can hint at what a student is feeling (e.g. confusion or frustration). Our first step is to implement a user-friendly system for sentiment detection on unoccluded faces. We are hopeful but unsure if this can be extended to masked faces.

Want to get to know your students better? Our app aims to provide a quick scan of their student ID that will show links to their resume (e.g. LinkedIn site) and social media pages.

Lastly, we also support the speech recognition feature that transcribes important information teachers might want to record during lecture time. It is often difficult to keep a memo while teaching at a fast pace. Teachers will be able to receive their transcribed memos from our website easily after class.

Example images

Project Description

instructAR (pronounced “instructor”) is an mobile app that facilitates classroom teaching experience for instructors. There are 3 features that we are proposing for the app:

-

Sentiment dectection with our original ML model: During the pandemic, many teachers are having a hard time learning how students are doing (e.g. confusion or frustration) in class due to mask mandates. Our first step is to implement a user friendly system for sentiment detection on unoccluded faces. We are hopeful but not yet sure if this can be extended to masked faces (that’s research?).

-

AR studentID: When teachers want to get to know their students better, they can use our app to scan a student’s ID card and a mini AR resume will pop out listing the key informations about a student.

-

Speak-into-text memo: Many times, teachers ask students to “Remind me after class” or “Remind me on Piazza” if a question arouses during lecture. However, this usually causes both parties to forget about the reminder. Our app aims to enable the speak-into-text feature for teachers to transcribe in-class announcements into text memos.

Problem Statement

Face Emotion Recognition (FER):

The COVID-19 pandemic has caused an unprecendent number of individuals to begin wearing masks on a regular basis whether it be for regulatory or personal reasons. In the classroom setting, teachers rely on student’s facial expression for cues on whether if students are understanding the lecture or not. In a masked classroom setting, face emotion recognition becomes challenging for the instructor.

However, deep learning models have been shown to be able to perform incredible tasks when given enough data. Thus, we want to investigate:

How well can deep learning models perform on face emotion recognition without information about the lower half of the face, namely, the mouth?

If this works even half of the times, it could aid teachers in identifying when students are confused over a complex topic.

Speech-to-Text Memo:

It is often times difficult for instructors to jot down reminders during class time especially if they are teaching with a blackboard. Switching between a pen and a chalk can get messy and annoying when the class is at a fast pace. Therefore, it would be very helpful if teachers can just record whatever they would like to keep a note of and retrieve the memo via their email (so that it would not get lost).

Contributions

Derek Zhang:

- integrated Keijiro’s port of MediaPipe models (Face Detection, Face Landmarking, and Iris Landmarking) into our “pipeline”

- created augmented AffectNet dataset (zero out lower half of face)

- trained and analyzed deep learning models for FER/eyeFER

- ported FER/eyeFER without locking up the app

- added depth to our pipeline and the depth visualization (using a world space canvas).

Chih-Yun Tseng:

- AR student ID

- Speech-to-text feature

- emoji overlay for sentiment dectection (without depth)

- app UI.

Challenges

Face Emotion Recognition (FER):

Face Emotion Recognition (FER) is a challenging task. In particular, the highest accuracy on AffectNet is 62.42% at the time of writing this report (source).

Keep in mind that AffectNet has just 8 categories. Compare this to the performance on ImageNet, which has thousands of categories. Deep learning methods have already acheived over 90% top-1 accuracy on ImageNet (source).

We have to deal with the fact that we’re creating a task, eye based face emotion recognition (eyeFER), that is even harder than an already hard task (FER)!

Not only did we have challenges with the high level task itself, we had multiple implementation challenges. We detail these below and their solutions follow later in this report.

First, despite being advertised as mobile friendly, EfficientNet was over 10 times bigger than BlazeFace (Face Detection). That meant you could not call the entire model in one update loop.

Secondly, we are proud of our method for grabbing the camera frames (for input to our computer vision models).

At first we tried using the XR ARSubsystem’s CPU Image. The issue was that we couldn’t easily align this image to the image rendered on screen (cropped and maybe zoomed in) (or rather we didn’t want to think about that).

Thirdly, if we updated the world object too frequently (in depth estimation mode), (visually) it looked like as if it was the same thing as drawing on a 2D canvas.

Speech-To-Text: Unity does not support native speech recognition.

Future Work

Software Engineering and FER/eyeFER:

One aspect of the app we can definitely focus on is optimization. In practice, we’ve found that the phone can get hot and this high power draw cannot be good for battery life.

For now this can be alleviated by using a bigger heatsink, such as a device as big as an iPad (this also has the benefit of a larger screen to see the student’s emotions). In the future, we hope that better hardware and software will increase the practicality of deep learning for mobile.

There are also latency issues since we have to run such big models on phones. The iPad would have more computer power and we should test our app’s performance on various devices.

With all these issues in mind, we could also consider running our big computer vision models in the cloud instead. However, the benefits of local compute is ease of scalability and privacy for the user.

Secondly, we can consider using more realistic methods of augmentation or covering the lower part of the face. Since we already have face landmarks, I can do more research into how we can overlay various masks artificially over the face. I’ve already come across a couple of papers that deal with overlaying synthetic masks. Given the fact that apps like Snapchat exist, I’m confident that this is a doable task.

We could even use more deep learning to do this. There has been work done the other way around by (N. Din et. al.) that explores using GANs to generate a realistic face without the mask conditioned on a masked face. You could use this GAN’s output to create a self-supervised task of undoing the mask removing.

Thirdly, our depth estimation only works for a single face setting. We will describe the technical reason in the following paragraph.

Keijiro’s MediaPipe ports use pre and post-processing steps that utilize shaders. Though Barracuda and the model supports batch processing, it’s unclear how to make shaders ingest batches as input. (This might be obvious to people who write shaders but my expertise is soley within the realm of Tensorflow/PyTorch.)

A simple method would be, for the input, use a for loop and concatentate the shader output for each image in the batch. Then, after executing the model, we can use another for loop and compute the shader for each batch slice individually.

We can also look into homuler’s port of MediaPipe that requires native compilation.

Fourthly, it could be worthwhile exploring how to make FER models more robust to face pose and lighting positions. I’ve found that varying the head tilt (with a static facial expression) causes the model to bounce around various emotions.

Perhaps there is a way to create a loss function that enforces smoothness on various head angles (which might require face reconstruction) and lighting conditions. I believe that such a loss may be costly to compute.

There are also datasets available for FER on videos. Using models that work with videos might help smooth out the predicted emotion. (Though we’d have to consider the computational cost given the limited compute budget on mobile devices.)

Speech-to-Text:

Future work such as denoising the raw audio file can be done in order to improve the accuracy rate.

Related Work

The two datasets we’ve looked into are FER2013 and AffectNet.

For FER2013, we found a PyTorch implementation using Residual Masking Networks that claimed an accuracy of 74.14%.

Why didn’t we use FER2013? Because it’s a black and white dataset and the residual masking network is massive. This is not optimal for mobile compute. (I will give credit that the repo does include an EfficientNet implementation but we had issues that I forgot to document.)

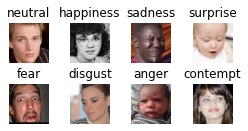

Regardless, what matters is that in the end we chose the AffectNet dataset. AffectNet contains over 400 thousand labeled images and the newest version includes 8 emotions:

This dataset wasn’t publicly available and we didn’t want to waste time requesting it. (At the time I didn’t think I’d need much data either. I might need the entire dataset if I ever want to make this a highly rigorous research project.) So I found a publicly available subset. After stripping out images where MediaPipe’s face landmarking failed, we were left with:

- 37394 Training Images

- 3987 Validation Images

As mentioned before, the current state of the art model is EfficientNet with a performance of 62.42% on AffectNet (at the time of writing this report).

Methodology

Face Emotion Recognition (FER)

What has already been done:

Barracuda is a “neural network inference library” that is the heart and soul of the project. It allowed us to run neural networks in Unity.

First, as far as libraries and SDKs that are free, we haven’t found any library more general than Barracuda for neural network deployment onto Unity. And as far as we’re aware, a port of MediaPipe into Unity is the best option. Mediapipe can handle everything up to face emotion recognition. Specifically, we use Keijiro’s port of three MediaPipe models: Face Detection, Face Landmarking, and Iris Landmarking.

Since we need to finetune a model for eyeFER anyway, we thought it be best to find a PyTorch model so we can train it. (There might be face emotion recognition plugins for Unity but we want to compare the effect of finetuning.) Hence, we used Barracuda to support all neural network ports.

As for eye based face emotion recognition, at the time of this writing, as far as I’m aware there isn’t research on this yet. What I turned up by searching on Google Scholar were papers on the effect of masks on humans performing face emotion recognition.

What Derek Did:

Derek was in charge of training, analyzing and deploying the models. For training and analysis, this was a machine learning problem done in Python. For deploying the models, this was a software engineering task done with Unity and C#.

First, I will document the technical details of preparing the dataset and training our model. All of the code is included in our GitHub repo under FinalProjectML.

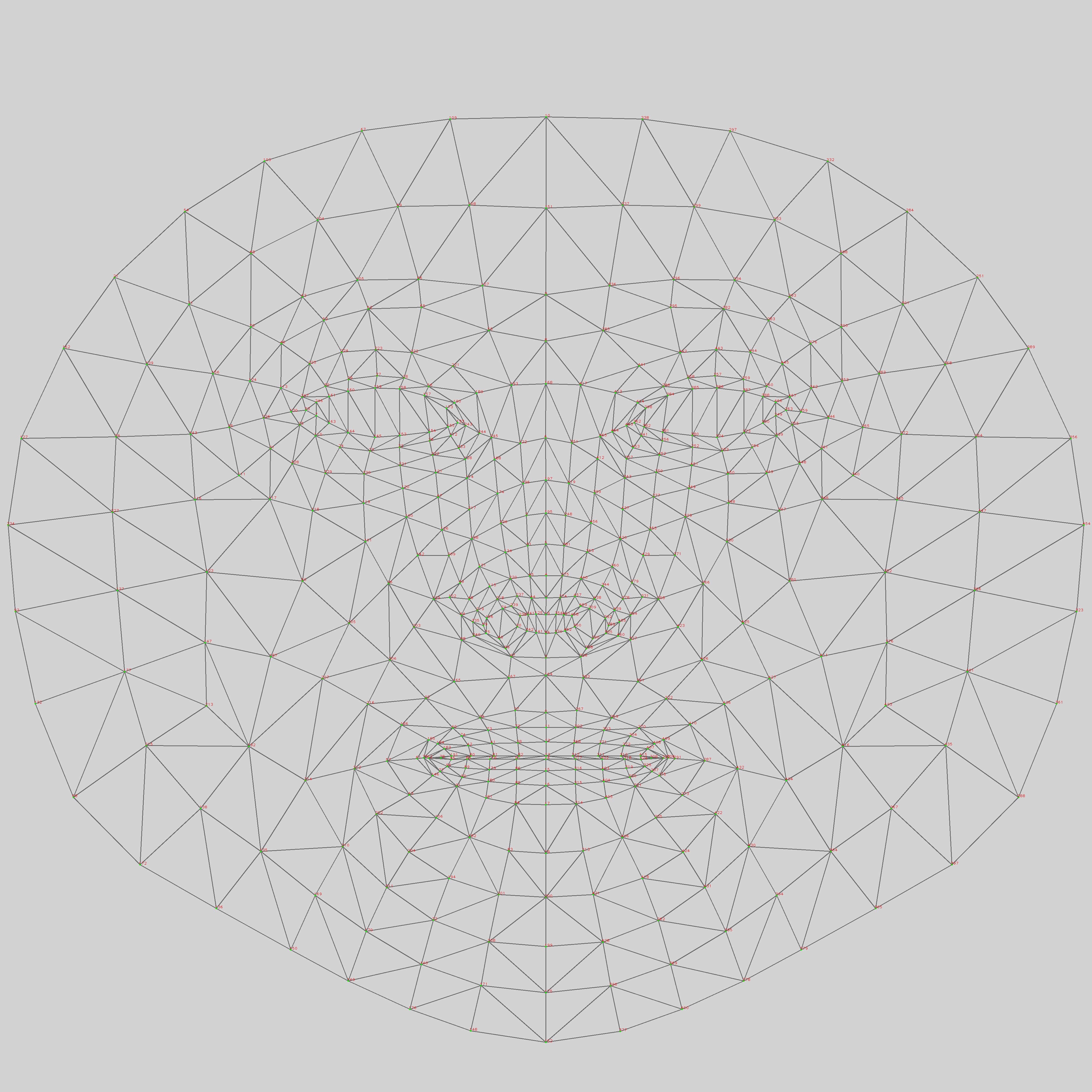

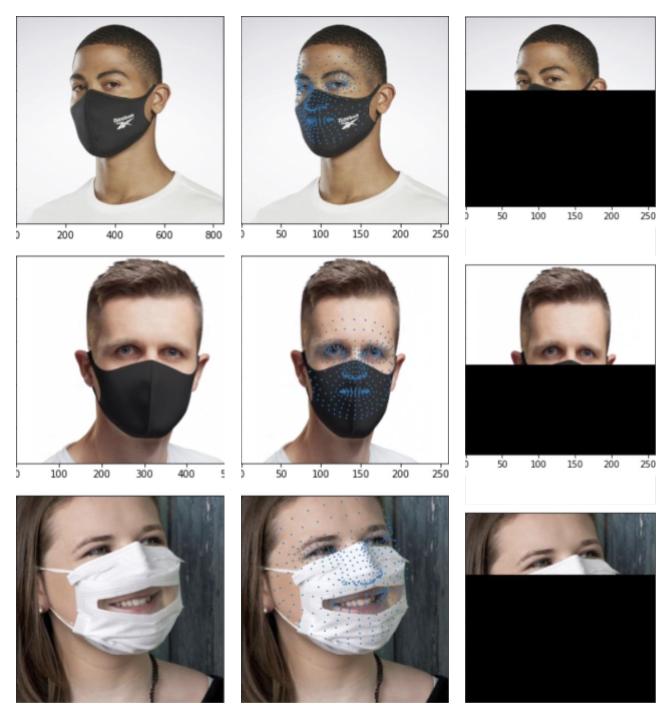

To create our augmented dataset, we used the MediaPipe library for face landmarking.

You can find their implementation on this repo.

We iterated over the original AffectNet dataset, ran this face landmarking for each image, and then stored the landmarks to disk.

Zero-ing out the lower half of the face can be done on the fly efficiently using numpy broadcasting. Hence, our data loader is responsible for loading in the images and using its precomputed landmarks to zero-out the lower half of the face.

We chose the nose point to be landmark #5 because it looked good. Masks worn properly cover part of the nose and this point seemed to be close to where the top of a mask would be.

MediaPipe FaceMesh Keypoints obtained from their repo.

Not only do we see in the above image that we are approximately zero-ing out the right area, but we also see that face landmarking works for masked faces.

The last important detail is regards to zero-ing out the face. Although we use the term zero-ing out, properly trained deep learning models always normalize their inputs. In this case, the model obtained from A. Savchenko’s repo used z-score normalization: (x−μ)/σ. We used the fact that after this normalization, the mean is mapped to zero. The mean was approximately RGB=(124, 116, 104). This is the color we actually used to zero-out the lower half of the face.

For this project, one consideration for zero-ing out the face rather than overlaying a synthetic mask was the ease of implementation. It’s trivial to implement in Python using numpy AND it’s as simple as setting a section of a Color array in Unity to a specific Color. We wanted to focus on testing the concept of eyeFER rather than be mired in porting Python pre-processing into Unity.

For training our model, we based our methodology off of A. Savchenko’s paper. In this paper, Savchenko first trained the model on auxillary tasks such as face recognition. Then, Savchenko finetuned this model on AffectNet.

Specifically Savchenko split finetuning into two stages. First, Savchenko trained the last dense layer (the classifier) with all other weights frozen for 3 epochs. Secondly, Savchenko trained the entire model (unfrozen) for 10 epochs.

For our purposes, I followed the same first stage but changed the second stage. Due to limited computational resources (and to make training time feasible), I elected to only unfreeze the last 2 convolutional layers and last 2 dense layers (which includes the classifier).

I ended up only using the model trained for 5 epochs instead of 10 because the model started to overfit (test loss curved back up). In retrospect, overfitting was another good reason not to unfreeze and train the entire model.

The overfitting warrants future investigation on whether if it was caused by the lack of data (maybe I should apply extra augmentations like horizontal flipping) or if it was caused by the extreme difficulty of the task itself (eyeFER).

PyTorch included functions to convert its models to the ONNX format, which is recognized by the Barracuda library. This allowed us to easily port the model architecture and trained weights into Unity.

Lastly, I wrote the code to combine all of the models together into one flexible pipeline. The user has the option to turn on eyeFER or depth estimation in the settings.

The following are the details regarding how I split the neural network compute over multiple update calls to prevent locking up the application.

We were lucky that Barracuda has support for manually calling each layer in the model. This made it possible to run large models without locking up the application.

We tried a couple examples written by the authors of the library and found that they all still locked up the screen. (For instance, we tried using a co-routine.) So we dug further into the documentation and used some inspirations from their example to create a new approach. In this new approach we budget compute using a precise Stopwatch and only call layers in the model while there is still time left for the current update call. This budget can be set in the editor.

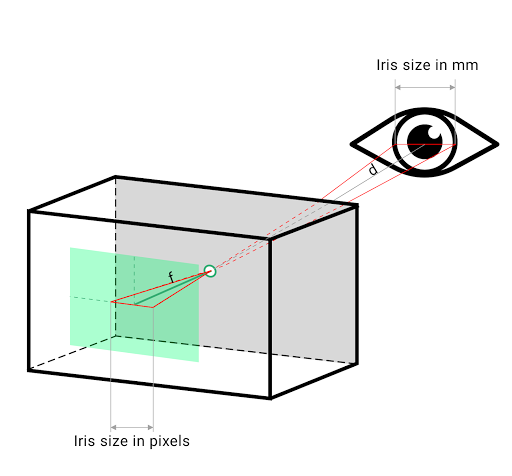

Iris Based Depth Estimation

What has already been done:

Since the iris is about a constant size across the human population (11.7mm with a very small margin of error), we can use this to estimate the depth of faces. We borrowed the math that uses similar triangles from the MediaPipe Github.

Above are images taken from Google AI Blog. We can see this is not a mad man’s idea and it actually works.

To reiterate, we use MediaPipe’s Face Landmarking and Iris Landmarking models to get the iris size in pixels. Then we obtain the depth by comparing the pixel size with its real world size of 11.7mm.

What Derek Did:

After obtaining the depth, we placed a world canvas at that depth from the camera, set the forward vector to be the same as that of the camera, and resized the world canvas size to match the frustrum. This allowed us to reuse the same code we used in the 2D case to place the emoji.

As mentioned earlier, updating a world space canvas too frequently lead to a non-AR experience. In my testing, I found that updating on fixed time intervals (1, 2, and 3 seconds) all did not achieve the effect that I was looking for. When we set the position of the canvas (and the emoji within), it looks like the emoji teleports.

The solution was to use a exponential moving average to detect when new predictions started drifting from past predictions. (Simple Euclidean distance with thresholding.)

This way, only when we detect that “where we thought the face was” is completely wrong, do we re-position the world canvas.

To summarize, the 2D face detection still runs every frame, but we choose not to visualize it until we detect a significant deviation.

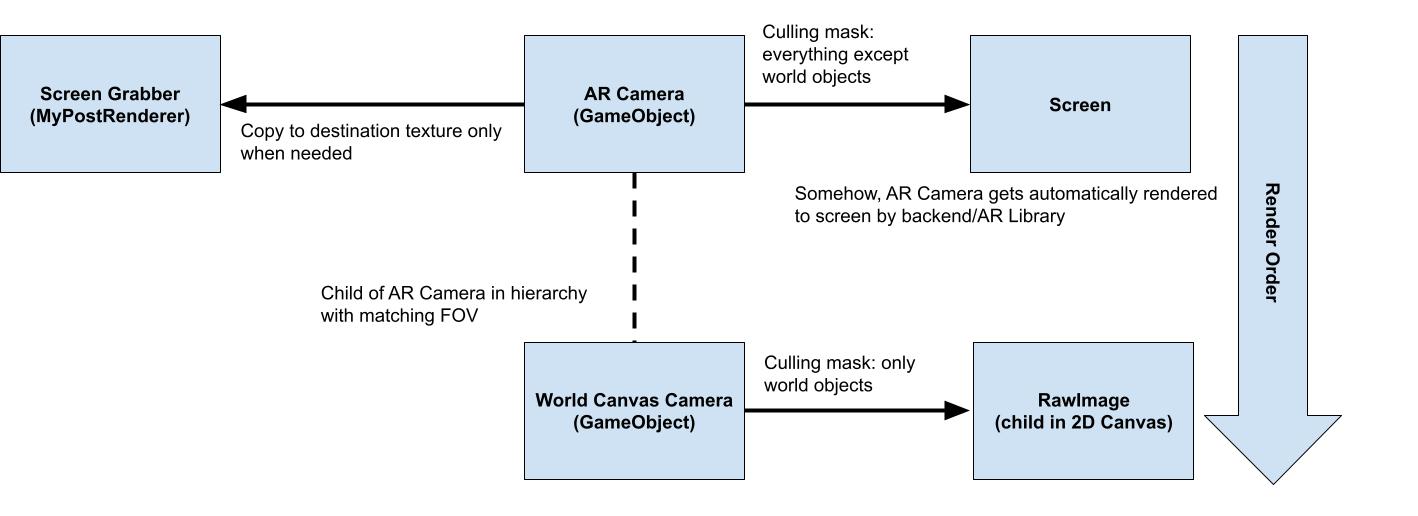

Next, I will detail our method for getting camera capture to work (somewhat) efficiently. We need this so we can feed the camera image as input to the neural networks in Unity.

Reverting our initial method introduced a problem where when we added an emoji to the world, that would get included in our screen capture. So after 1 frame of visualization, the original face is no longer detected because it’s occluded with an emoji.

In the end we used two cameras with different culling masks to resolve this as shown below. Please note that although the final rendering of world objects is to a 2D Canvas, this is AR with depth. We are just handling the ordering of rendered objects manually. Doing so allowed us to exploit intermediate layers of rendering, which was vital for our method to work.

AR Student ID

This is built with the Vuforia engine. Vuforia supports image tracking which is very helpful for this feature. We set our UMD student IDs as image targets and then created game objects in Unity that serve as our AR cards.

Speech-to-Text Memo

At first, we wanted to see if there is any built-in support in Unity for speech recognition. However, most online sources are out-of-date or are not compatible with our devices (iOS). Some online blog posts suggest writing a wrapper that takes the speech recognition library (in Object-C) and turns it into C# code. This solution is quite hard to implement as we are not familiar with both languages (seems like the wrappers are based in CPP and also require knowledge of what Unity supports). Therefore, we chose to use Python which has well-established speech-recognition libraries (the one we are using is the google speech recognition).

However, we soon realized that Unity does not support Python in any way. It has a pre-released Python package that is only functional in Unity Editor, which means any Python code would not run after build. Thus, we decided to run Python externally and host a website that can process speech recognition without having to mess with Unity. As a result, audio files are now uploaded to our Firebase Storage and user information is uploaded to Firebase Firestore. The reason that we use both Firebase Storage and Firebase Firestore is that audio files (e.g. wav files) cannot be stored in a normal NoSQL database. We have tried to convert the audio file into a byte array and recover it into a wav file but the content gets very distorted and often times it would not even work. The two databases communicate with a special key that is auto-generated whenever users hit the “save” button in our app. The probability of a key collision is extremely small (in fact, 1/3610).

When users want to retrieve their speech-to-text memo, they can click on the “Speech-to-Text” button on our app and visit our website and fill out a query to our backend. Our backend first checks whether the specified file has been processed before. If so, then it fetches the corresponding text memo from Firebase Firestore and sends the txt file directly to the user’s email address. If not, then our backend fetches the audio file from Firebase Storage and performs speech recognition internally. Before doing speech recognition, we filter out ambient noises that may affect the conversion. This is important because google’s speech recognition library is pretty sensitive to pre-recorded audio (i.e. a recording of another recording) and background noise. Lastly, it will update the speech-to-text result to Firebase Firestore to prevent redundant processing in the future.

Results & Analysis

Demo

- Face Emotion Recognition Demo

- Speech-to-text Youtube Demo

- AR Student ID

eyeFER on Paper

Terminology

- AffectNet - The original dataset (we used a subset that was publicly available). All other AffectNet datasets types mentioned are created by transforming this dataset in some way.

- Augmented - We performed face landmarking on the images in the dataset and zero-ed out the pixels below the nose line.

- Compressed - The emotions are redefined as follows:

- activated - fear or surprise

- irritated - anger or disgust

- neutral - neutral or contempt

- happiness - happiness

- sadness - sadness

Figures

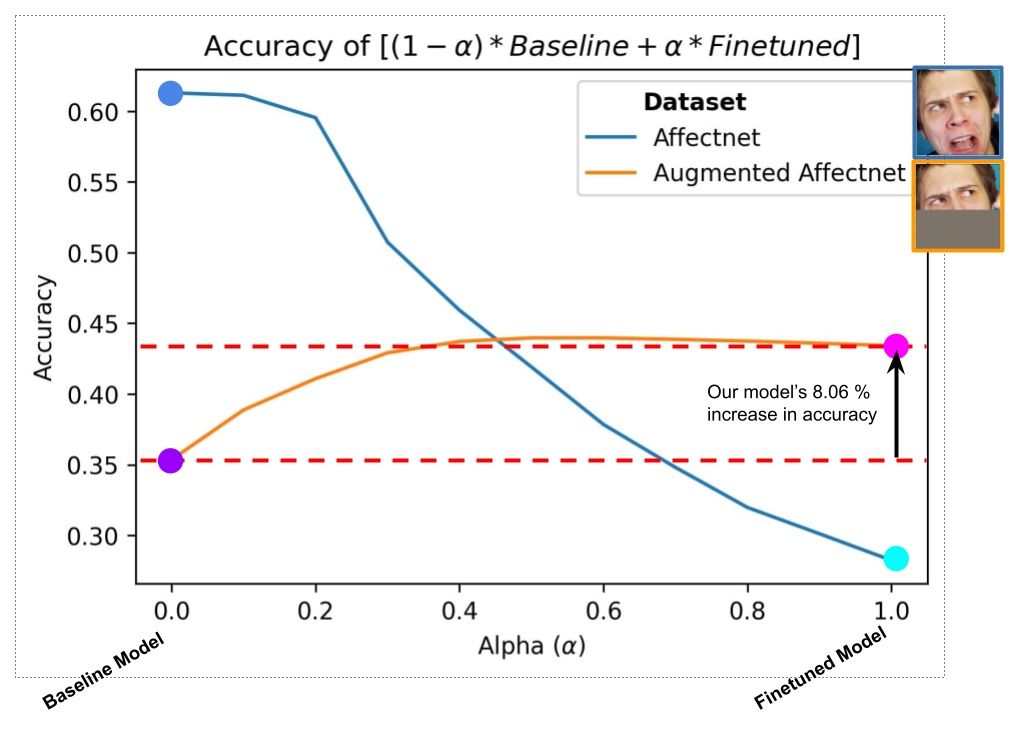

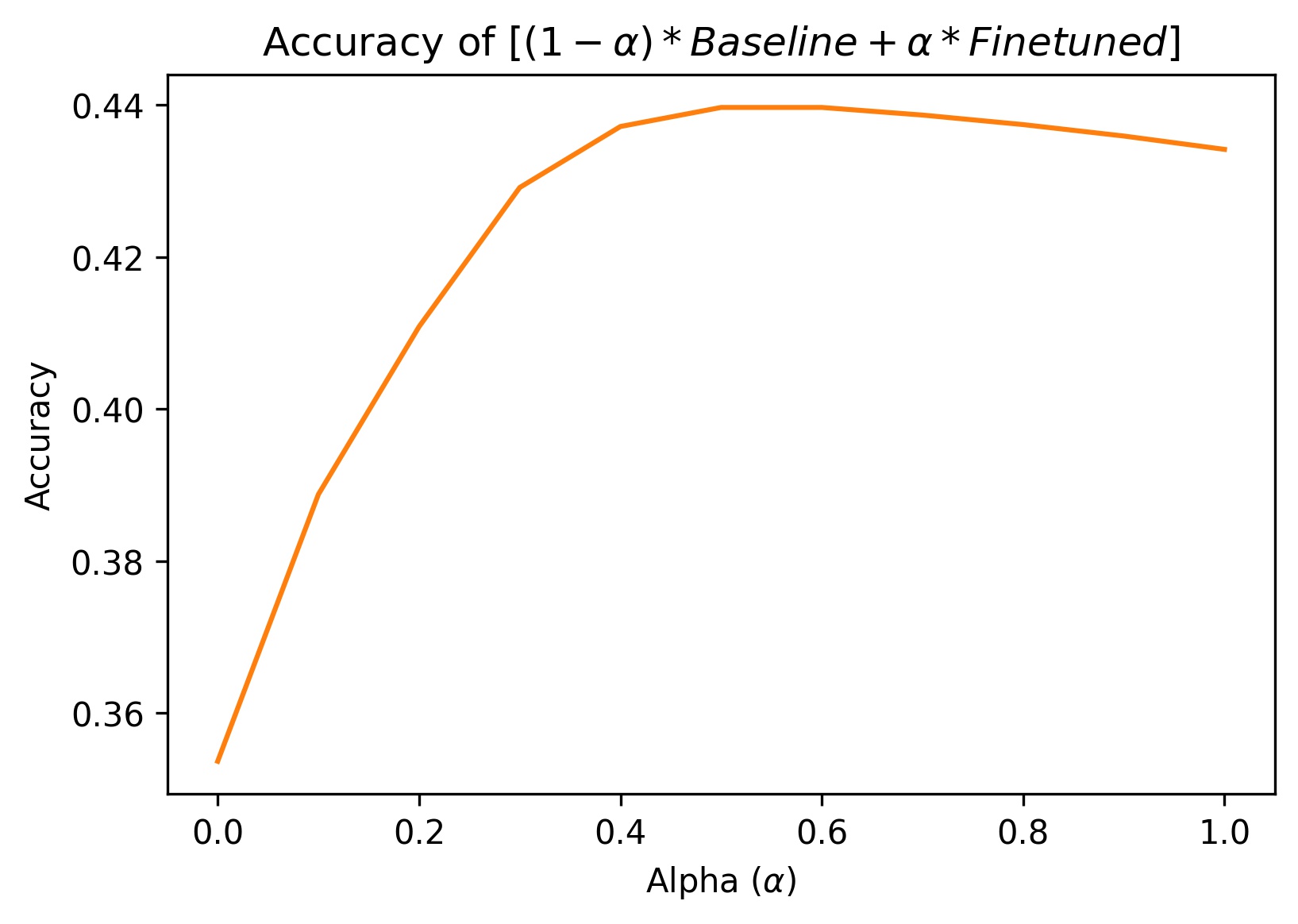

Figure 1 - Left: Ensemble model using weighted average on baseline and finetuned. Right: Zoomed in on the peformance on the augmented dataset (to better show the shape and characteristics of the curve).

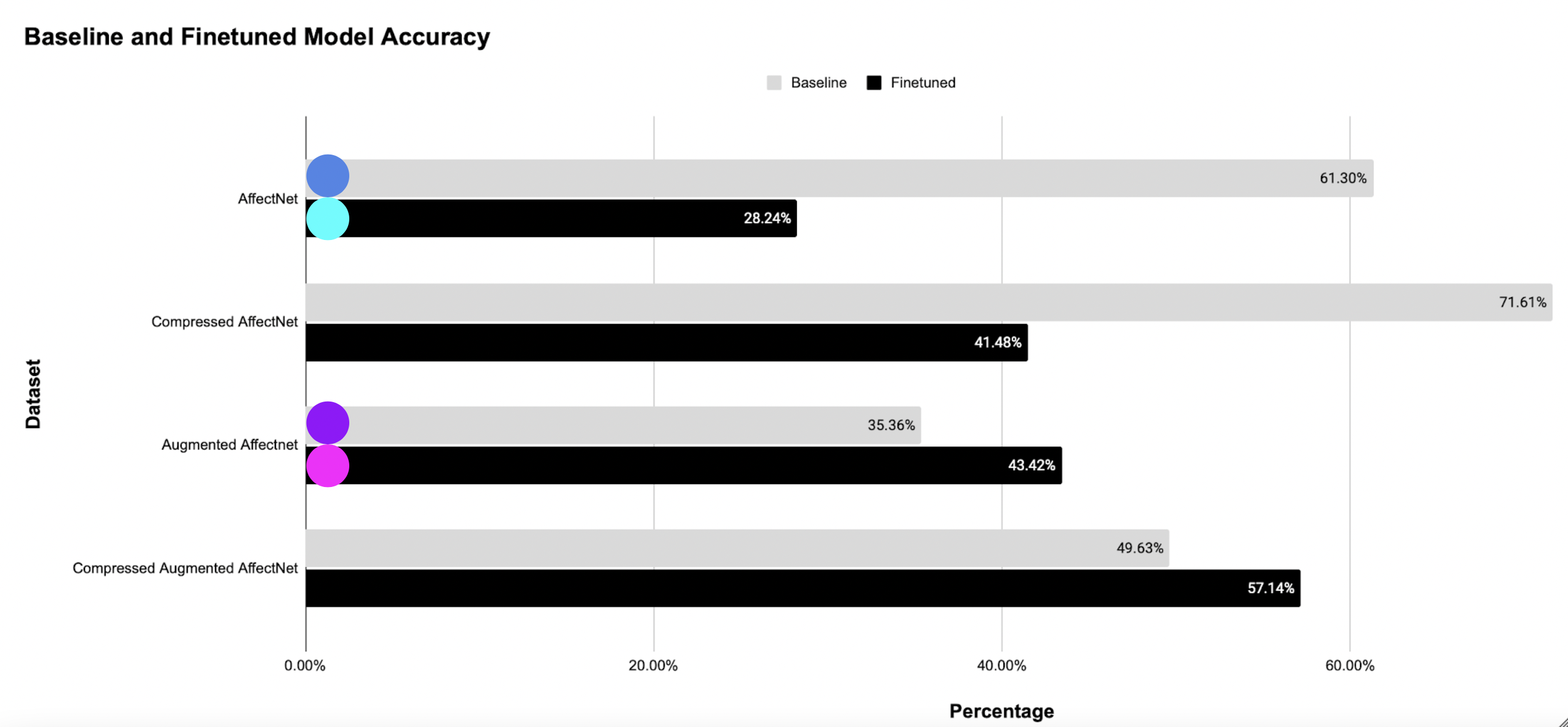

Figure 2 - Comparison of accuracies between the baseline and finetuned model on various dataset transformations. Note that the colored circles directly map to points in fig. 1.

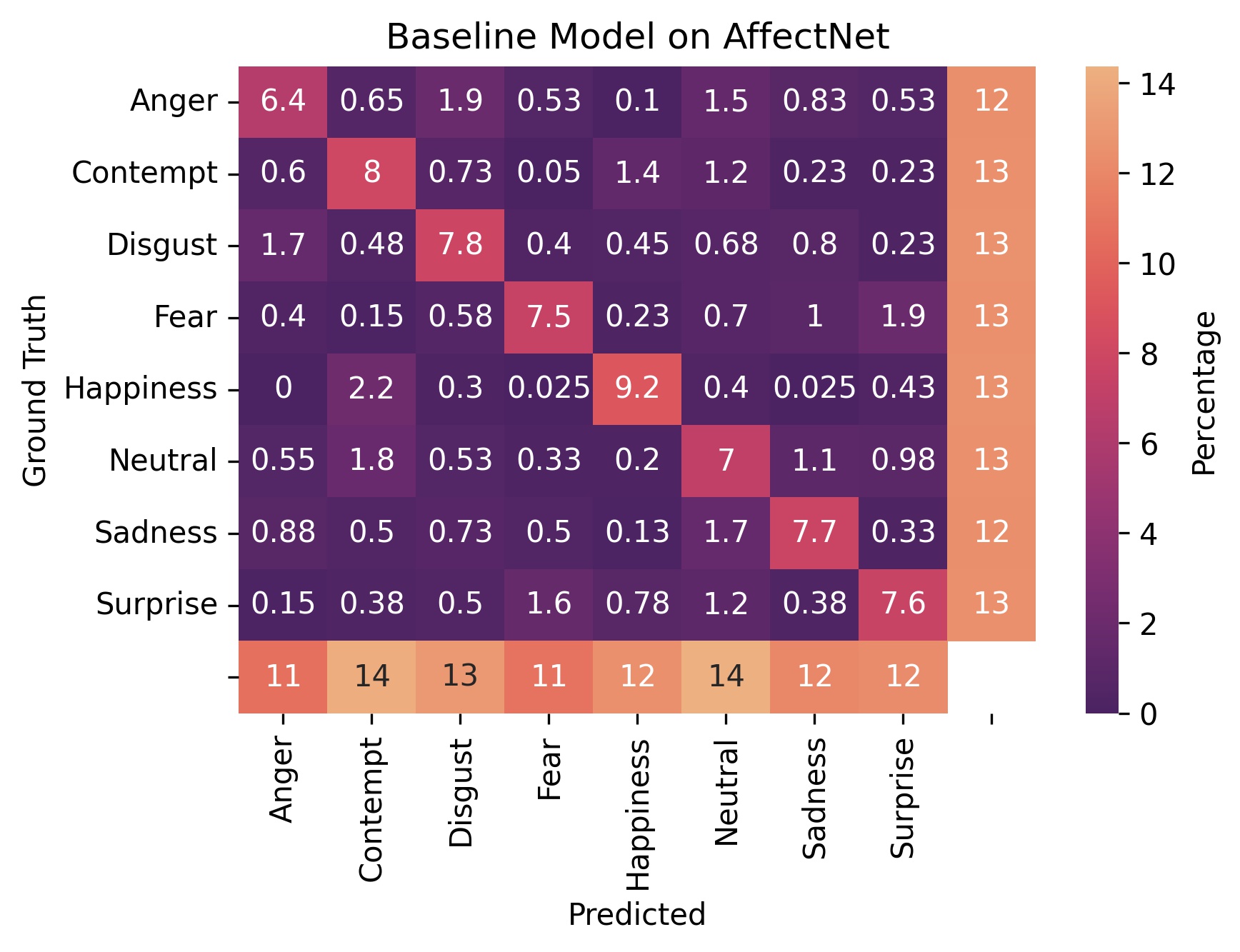

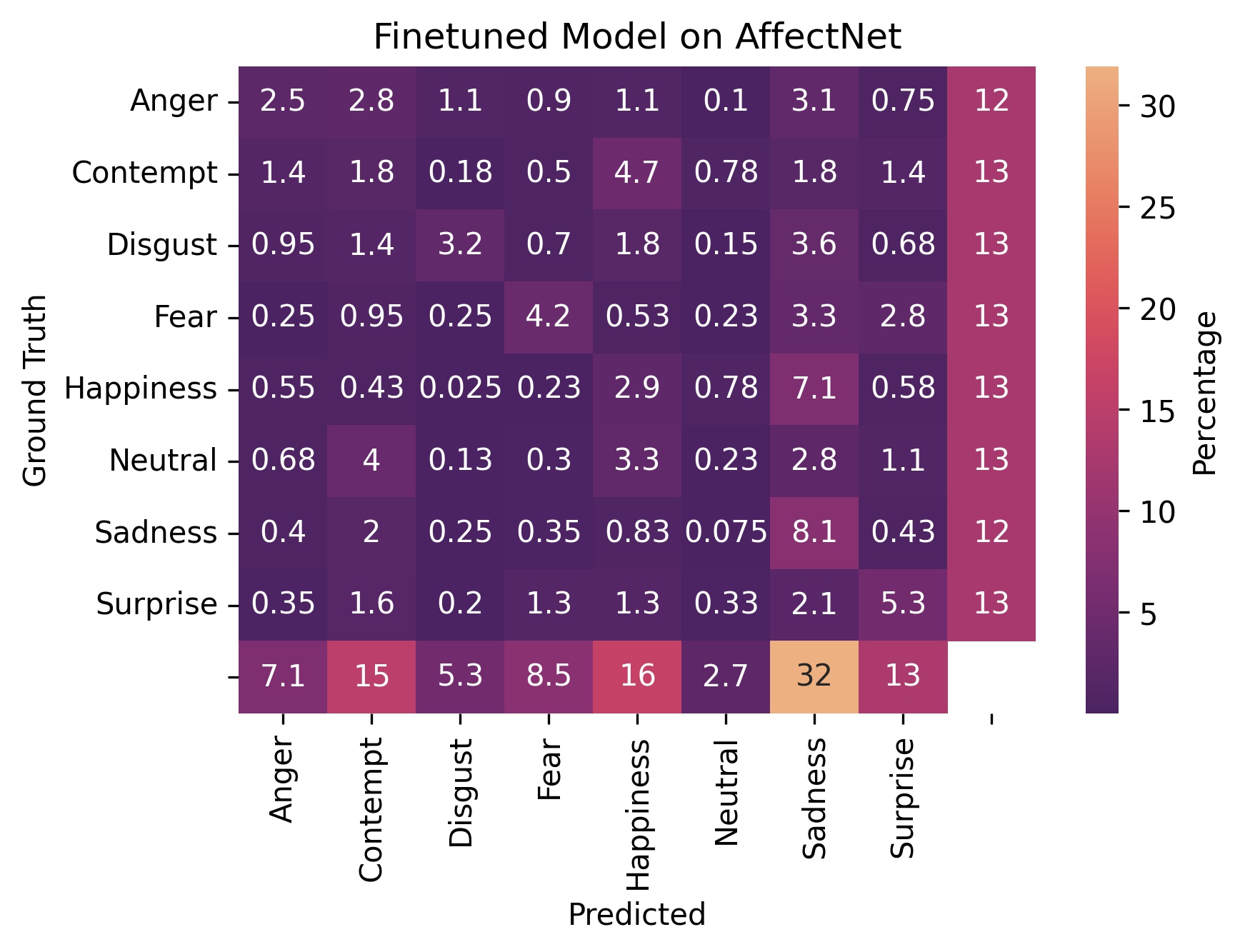

Figure 3 - Confusion matrices on the original AffectNet dataset. The margins show the row and column totals.

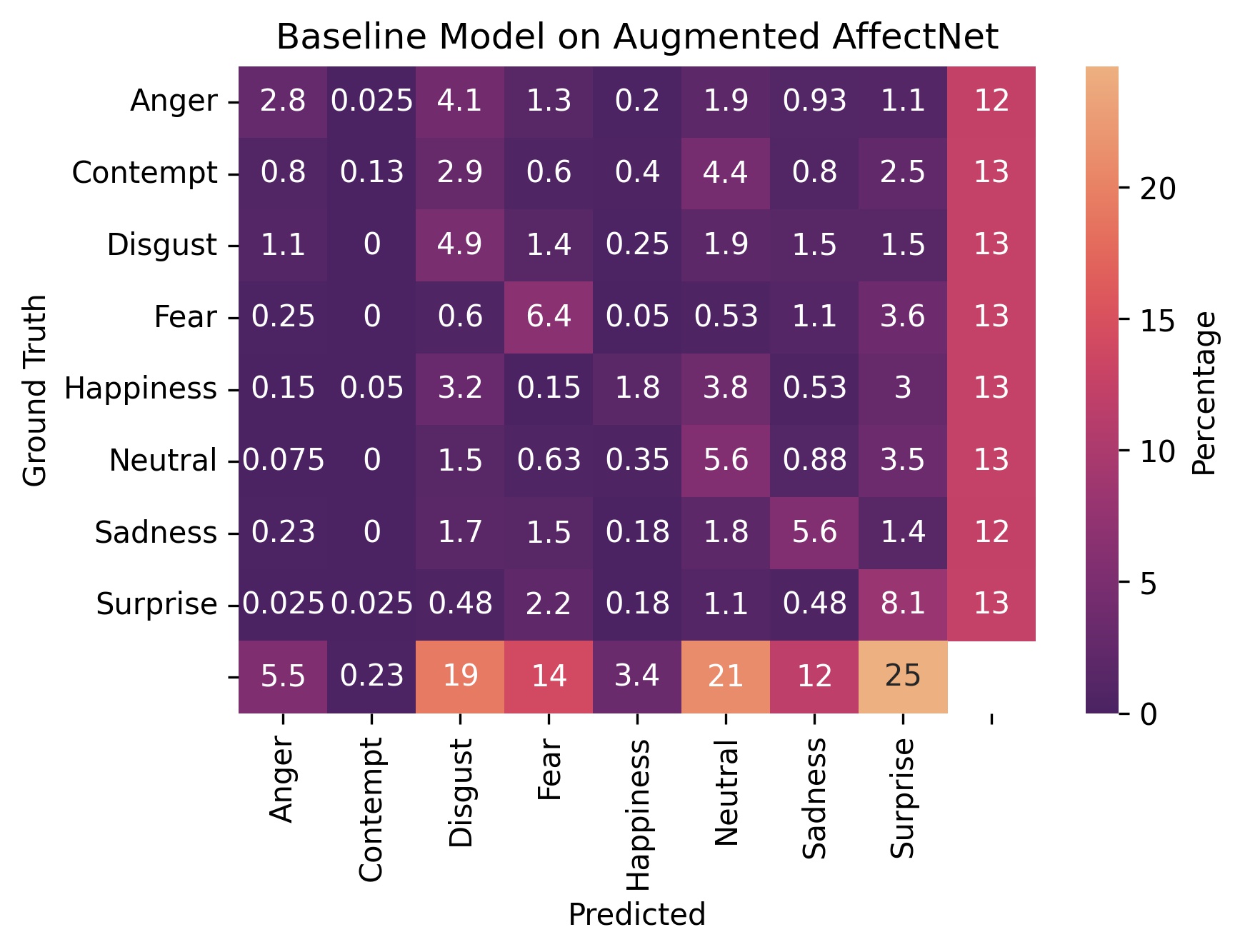

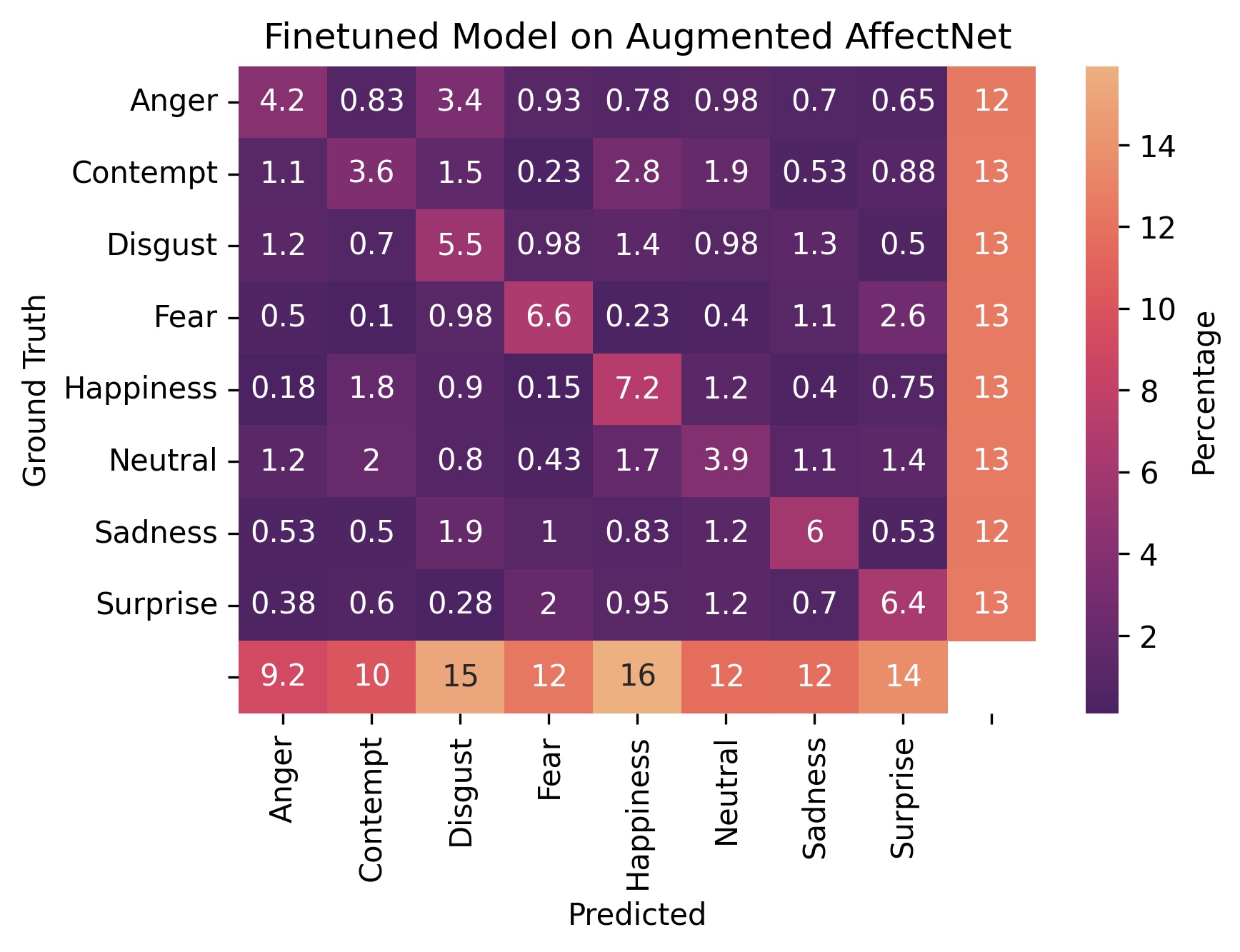

Figure 4 - Confusion matrices on the augmented dataset where the lower half of the face is removed.

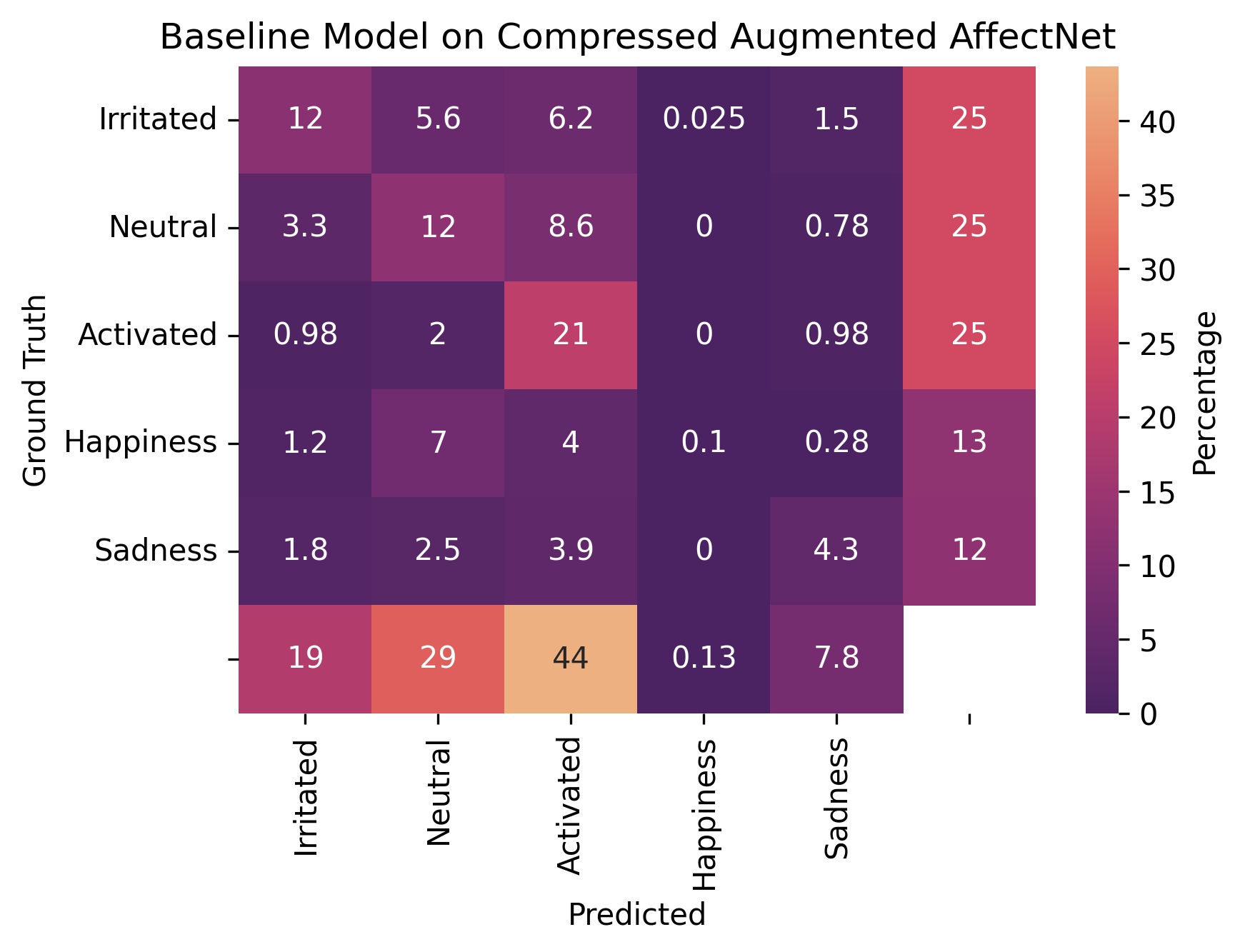

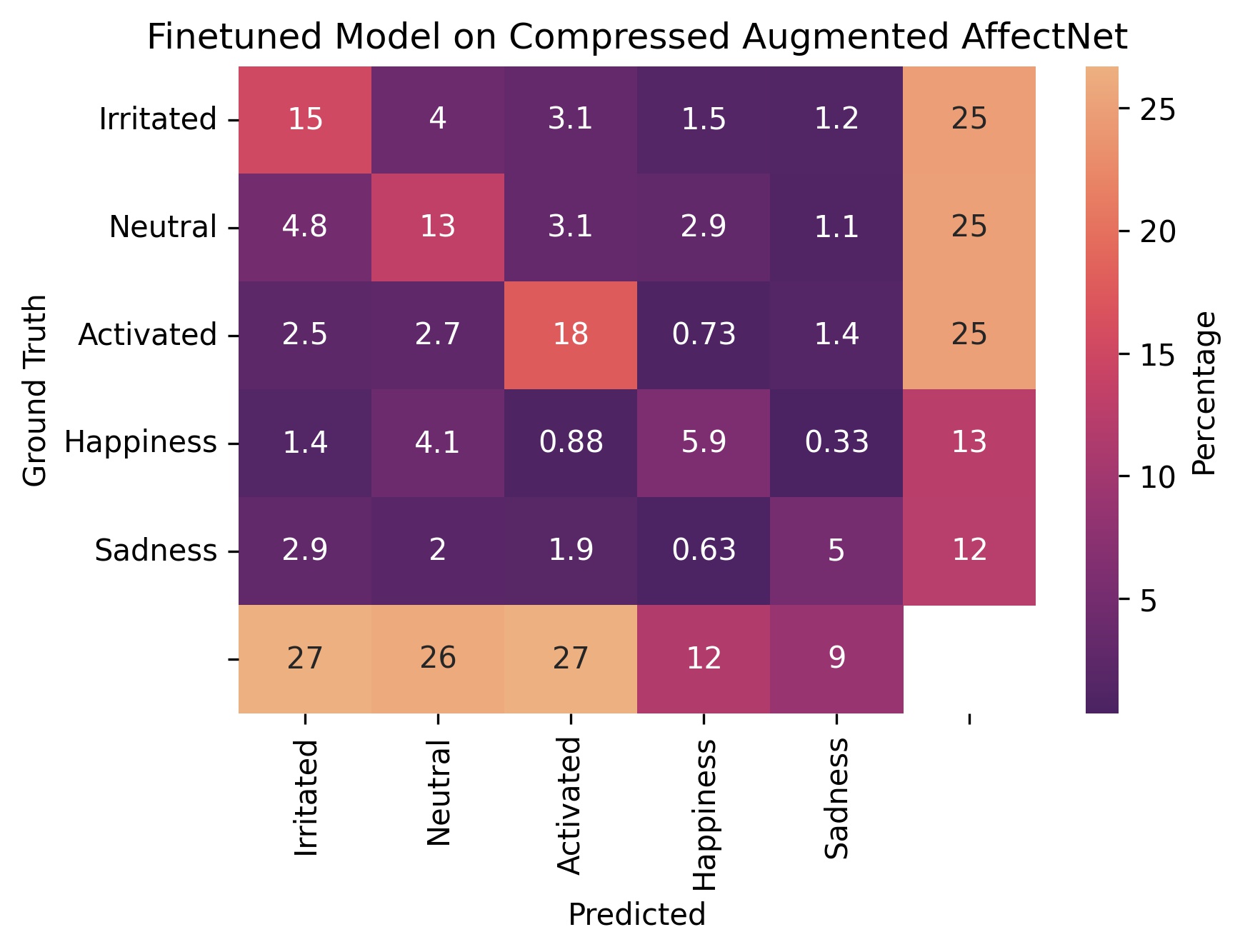

Figure 5 - Confusion matrices on the augmented dataset where the lower half of the face is removed and evaluation with compressed emotions.

Analysis

In figure 1, we weighted our baseline and finetuned model’s output (predicted probabilities for the 8 emotions) by α and 1-α respectively to create an ensemble model.

The blue curve in fig. 1 actually is to be expected. This curve represents our ensemble model’s performance on the original AffectNet dataset. I hypothesize that our finetuned model performs so poorly because of how we augmented the dataset. By zero-ing out the lower half of the face, the feature activations related to the mouth and any lower part of the face are always zero. This would be true all the way to the last layer, which our finetuning optimizes. So when we perform gradient descent, the weighting on these features never gets any signal. Basically, the eye based features never learn to “play well” with the presence of mouth features.

Thus it is somewhat unfair to evaluate our finetuned model on the original dataset with full faces. And in practice, we argue that this full face problem isn’t a problem at all. The presence of a face almost always means that we can perform landmark detection. So that means we can easily zero out the lower half of the face before feeding it into our finetuned model. Our eyeFER model will always get input similar to its training set, the augmented dataset. In our app, we always use face landmarking to zero out the lower half of the face before feeding the face into our eyeFER model.

This does lead us to be curious. What if we also trained a mouthFER? Would ensembling such a model with eyeFER lead to even decent results? And would adding a finetuned layer (for cross eye/mouth feature relations) get us anywhere close to SOTA?

The orange line in fig. 1 shows the ensemble performance on the augmented dataset. Though this is also somewhat of an unfair evaluation since the baseline has never been trained on the augmented dataset, we argue that there is still value to this analysis.

For one, this curve shows that the finetuned model contributes more to the performance on the augmented dataset than the baseline. We know this by comparing the steepness on both sides of the curve (split at α = 0.5). It is interesting to note that at around α = 0.5, we get a very small bump in performance.

Secondly, we can also treat this analysis as what happens when we zero out activations for mouth related features. (Though it’s less clear how this affects deep features that depend on both shallower eye and mouth features.)

Even though we have to take fig. 1 with a grain of salt, we created this graph because we think it is an interesting way to present our results.

From fig. 2 we see that the baseline model scored 61.3% on the original AffectNet dataset and the finetuned modoel scored 43.32% on the augmented dataset. We also see that our model scored 57.14% when evaluated on the compressed augmented dataset.

This looks like as if we need a handicap to even come close to SOTA. Even if we did, that is impressive given the fact that we have no mouth to work with! But let us consider this from another perspective.

The baseline model managed to score a whopping 71.61% accuracy when evaluated on the compressed original dataset.

We lose almost 26 points when we evaluate the baseline on the augmented dataset and we lose almost 22 points when we evaluate it on the compressed augmented dataset.

Compare this to our finetuned model. Our finetuned model scored 57.14% on the compressed augmented dataset. This is a loss of 14.47 points. Not great but, at least on paper, we are less inaccurate than the baseline!

Keep in mind, some papers are published when they even get just a few points of increase in accuracy. Here, we are likely pioneers. At the time of this writing, it is likely a vacuous truth that we have trained the best eyeFER model in existence!

Figures 3 through 5 are our confusion matrices. A strongly lit up diagonal indicates that a model is doing well on that particular dataset.

In fig. 4, we can see that our finetuned model really did make improvements on our augmented dataset. The diagonal on the finetuned model’s confusion matrix is more pronounced than that of the baseline model.

We can see in the margins that for figures 3 and 4, the test dataset is balanced.

An interesting phenomenon is that in fig. 5, the distribution (likelihood) of the finetuned model’s predictions matches that of the compressed test dataset. However, the baseline is all over the place with a very strong bias towards predicting “activated”. (We can see this by comparing the margins).

eyeFER in Practice

So far we’ve only mentioned how we believe, in theory, that our finetuned model works. In this section, we present feedback obtained in the field and from real people.

Student Testimonies

“I was impressed with how consistently the app could predict my mood even with a mask on.” - Garrett (UMD Computer Science Undergrad)

“This is actually really useful.” - Sahil M. (UMD Computer Science Undergrad)

Feedback from Professionals

How useful would this app have been to your teaching in a masked classroom setting?

- “4/5” - Dr. Raymond Tu (UMD FIRE Capital One Machine Learning Faculty Leader)

- “4/5” - Dr. Stefan Doboszczak (UMD Department of Mathematics)

Of course, we also report on negative results:

What emotions does the model seem to get wrong when you wear a mask?

- “Happiness” - Garrett

- “All emotions, but it’s expected” - Dr. Tu

- “Irritated” - Dr. Doboszczak

How useful would this app be once masking in classrooms becomes optional?

“2/5” - Dr. Tu and Dr. Doboszczak

It’s clear that once the pandemic has abated, eyeFER will not be very useful in all but the most niche scenarios.

However, after reading papers analyzing the effect of face masks on various populations such as individuals with autistic traits, I’ve realized that we may be able to flip this technology around. Hence, I remain hopeful that, even if no teachers want to use our app post pandemic, we can use this to help students with mental disorders.

Speech-to-Text Memo

- Our website for speech-to-text memo

- Analysis: We tested the speech recognition feature on the following variables: content complexity, speaker fluency, and with/without wearing masks. For content complexity, we have two scripts where one is just a casual note that does not involve any uncommon/professional vocabulary and another that contains special vocabularies used in the math field. For the casual script, the result for both speakers are around a high 90% accuracy (with and without wearing a mask). However, our second script had more complicated vocabularies like “Lipschitz” as well as homophones “Rn” and “Rm” where the letter “n” and “m” can be easily confused. Our result shows that the speech recognition has a lower accuracy for the speaker with accent in this context. Nonetheless, the speech recognition feature can precisely distinguish even “n” and “m” for the native English speaker. Finally, all test results showed that speech recognition with masks is more difficult than without masks.

AR Student ID

See demo in earlier section.

May 18th Project Presentation

498F_838c_final_project_presentation.pptx

April 28th Project Progress Report

498F/838c_final_project_progress_report.pdf

April 5th Project Proposal

498F/838c_final_project_presentation.pdf

Instructions

- When running the project on Xcode, be sure to run the entire build file (open from the root folder) and not just the xcodeproj file.

-

Speech-To-Text recording instruction:

- If you would like to perform queries on the database, please make sure that the specified email address and filename exists, and that the date is also relevant. By default, if an user only inputs their email address, they will receive all memos since May 1st 2022.

Links to our source code

References

- Speech-to-text

- AR student bussiness card

- Sentiment Detection Model

- Affectnet Dataset

- Affectnet Subset (that we actually used)

- Face Emotion Recognition by A. Savchenko: paper and code.

- Barracuda

- Keijiro’s ports of MediaPipe to Unity using the Barracuda library: BlazeFace, Face Landmark, and Iris Landmark.

- MediaPipe (mainly for the face landmark model which we used to create the augmented dataset) and their GitHub where we found math for iris size to depth.

Acknowledgements

- My roommate Garrett who was always willing to be my test subject and help me test the app.

- My friend Sahil for supporting me this semester and helping me test the app.

- My former professors Dr. Tu and Dr. Doboszczak for helping me test the app.

- Dr. Ming Lin and Nick for making this class possible.

- Nick was very approachable and gave great advice.